Paradise, Sovereignty and Aesthetics under the Great Mughals

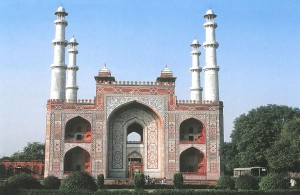

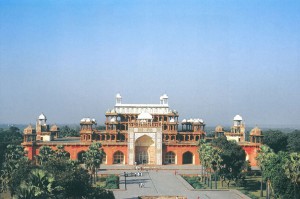

The Mughal emperors harnessed the desire for paradise – the essential focus of Muslim piety – to buttress their claim to rule as God’s vicegerents. Perceiving themselves as mediators between heaven and earth, their attributes for this role were manifested through their beneficent rule. As a natural corollary imperial aesthetics associated beauty (jamal) with majesty (jalal) as expressed in architecture and the arts; and under Shahjahan paradise became the supreme visual metaphor for the emperor’s rule.

The Mughal emperors harnessed the desire for paradise – the essential focus of Muslim piety – to buttress their claim to rule as God’s vicegerents. Perceiving themselves as mediators between heaven and earth, their attributes for this role were manifested through their beneficent rule. As a natural corollary imperial aesthetics associated beauty (jamal) with majesty (jalal) as expressed in architecture and the arts; and under Shahjahan paradise became the supreme visual metaphor for the emperor’s rule.

Shahjahan achieved the aesthetic apogee, further extending the role of the arts in the presentation of sovereignty, associating beauty with majesty. The supreme expression of sepulchral architecture in the Taj Mahal, designed as a prefiguration of heavenly paradise, was complemented by palaces and gardens and the construction of a new capital described by a contemporary chronicler as composed of paradise-resembling edifices.

In the palace of Shahjahanabad, the Nahr-i Behesht, River of Paradise, threaded through the imperial apartments and the zenana; the jharoka – throne in the Diwan-i Am (hall of public audience) recalled the throne of the prophet-king Solomon; and the inscription on the Daulat Khana-i Khas (hall of private audience) proclaimed “if there is a paradise on earth it is here, it is here, it is here”.

This article will examine how imperial patronage of the arts, through architecture, painting, and court etiquette, was designed to associate the emperors with paradisial imagery thereby manifesting their unchallengeable right to rule.