A Taste for Green Space: Landscape of the Ancestral Lands and the Mughal Dynastic Image

Philippa Vaughan

Forging a political and cultural legitimacy to underpin the fact of conquest was a primary dynamic of Mughal polity in the early years of the dynasty, and elaborating images of legitimacy remained a concern for Shah Jahan. Allusions to the Timurid cultural inheritance thus underpinned much imperial imagery and architecture as a legitimising element. The first architectural expression was the tomb of Humayun in Delhi, constructed 1562-1571 in the early years of Akbar’s reign: the monumental proportions, characteristic of imperial Timurid architecture proclaimed the Mughal lineage; the dome-centred radial design known as eight paradises (hasht behisht) was recognisable from Timurid prototypes; the fact that a monumental tomb was constructed so soon after Akbar’s accession when his hold on power remained tenuous, showed the dynasty intended to remain in India (Babur’s body had been taken to Kabul for burial). The innovation of a garden enclosure on a vast scale recalled the Timurid bagh in which most royal ceremonies took place; as also did the planting, with meadow set between the raised walkways and channels in a manner appropriate to the ceremonies and to the huge scale of the building.

Forging a political and cultural legitimacy to underpin the fact of conquest was a primary dynamic of Mughal polity in the early years of the dynasty, and elaborating images of legitimacy remained a concern for Shah Jahan. Allusions to the Timurid cultural inheritance thus underpinned much imperial imagery and architecture as a legitimising element. The first architectural expression was the tomb of Humayun in Delhi, constructed 1562-1571 in the early years of Akbar’s reign: the monumental proportions, characteristic of imperial Timurid architecture proclaimed the Mughal lineage; the dome-centred radial design known as eight paradises (hasht behisht) was recognisable from Timurid prototypes; the fact that a monumental tomb was constructed so soon after Akbar’s accession when his hold on power remained tenuous, showed the dynasty intended to remain in India (Babur’s body had been taken to Kabul for burial). The innovation of a garden enclosure on a vast scale recalled the Timurid bagh in which most royal ceremonies took place; as also did the planting, with meadow set between the raised walkways and channels in a manner appropriate to the ceremonies and to the huge scale of the building.

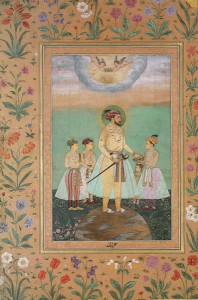

The first pictorial representation of “dynastic landscape” is probably “Princes of the House of Timur”. Shah Jahan, like his predecessors, ordered his principal painters to rework the image but also commissioned new ones following this topos which, while aesthetically dull, clearly were highly prized since they appear as the opening double page in of one of Shah Jahan’s Albums. The additional feature of the flowering meadow in which the courtiers stand is significant. This is not an isolated example of meadow being associated with dynastic portraiture.

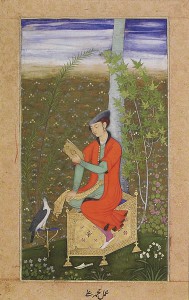

Meadowlands were beloved by Babur who notes many outside Samarqand by name:

“All around the city are exquisite meadows, including the famous Kan-i-Gil…The rulers of Samarqand have always made this meadow a protected reserve and come out every year to stay for a month or two. Higher up is another meadow, the Khan Yurti…another is the Bodana Qorughi…Another fabulous meadow is the Lake Mughak meadow…During the seige of Samarqand, while I stayed in Khan Yurti, Sultan-Ali Mirza stayed there. Another fairly small one is the Qolba meadow…to the south is the Bagh-i-Maydan and Darwesh Muhammad Tarkhan’s chaharbagh ..for pleasure, good air and superb vista few are like it. It is situated on a rise overlooking the Qolba meadow so that the entire meadow lies stretched out below it.”

Outside Kabul there were Song Qorghan, Chalak, Diurin, and the Siyah Sang meadow. Babur’s comment that the latter “is not much maintained because it attracts so many flies in summer” shows that meadows normally were carefully tended.

In his love of green space—of meadows, of grassy plots (chaman), clover (seh barga), and shade trees, and his creation of view points from which to enjoy the landscape—Babur reflected his Timurid lineage. Effectively he described a landscape identified with the dynasty.

The setting of meadows is used in a highly important portrait of Prince Khurram 1616-17, suggesting that this setting was more than a decorative motif for generic portraits.

The image of Shah Jahan as a prince, holding a jewel, placed within a flowering meadow, was painted by Jahangir’s leading court artist Nadir uz-Zaman c.  1616-17.

1616-17.

The dramatic setting for a single image resonates with references to the landscape beloved by Babur. It appears as a touchstone recalling Mughal ancestry and images of legitimacy, and is repeated in the dynastic portraits produced early in Shah Jahan’s reign. Shah Jahan took possession of the throne only after a bitter and fratricidal struggle. Moreover Timurid blood in the imperial veins had been quartered in the past two generations, since both Jahangir and Shah Jahan had been born of Rajput mothers making Shah Jahan only one quarter Timurid.

While Mughal rule seemed established in the capitals of north India, and the architecture and ceremonial provided a visual metaphor for its legitimacy and authority, continual recollection of the Timurid cultural roots was required to buttress long cherished claims to Balkh and Badakhshan. Regaining control of these ancestral lands remained a dynamic of Mughal foreign policy until 1675 when Emperor Aurangzeb, who had led many of the expeditions while still a prince, finally abandoned them in favour of conquest of the Deccan.